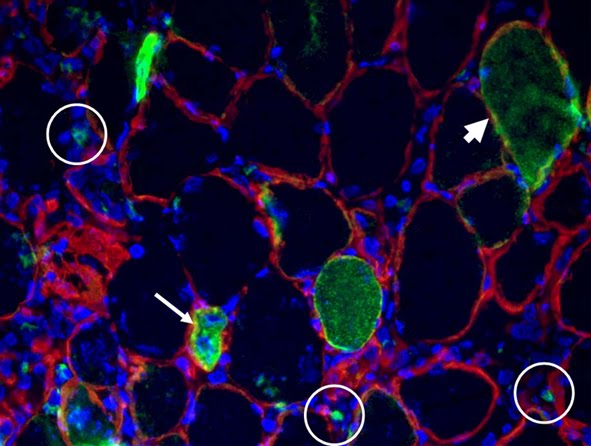

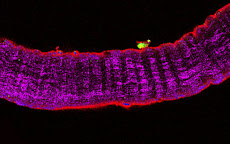

FIGURE LEGEND: Cross-sectional view of a Tibialis Anterior injected with GFP DNA (green), electroporated in our Roman lab following Donà et al., and immunostained for laminin (red).

Some times a scientific article is outstanding because of its breakthrough findings, some times it is particularly elegant in its demonstrations, some other times an article is just so useful! The following are some of my favourite methodological papers.

For people working on gene delivery by electroporation to skeletal muscle tissue, Donà et al. carefully address which are the best settings for the square wave electroporator. The efficiency of this approach can be pretty high, as shown by this article and by the image above. We often perform electroporation-mediated delivery of two different plasmids with the aim to obtain co-expression. Which is the correct ratio between the two constructs? For instance, if we want to co-express Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) as an expression marker, which amount of the plasmid of interest must we combine with the GFP to be sure that it is expressed by the fibers that turn out green? Rana et al. have found that co-expression rate between BFP and GFP in skeletal muscle is about 100% in their experimental settings.

A caveat on the use of GFP comes from this paper by Goodell and co-workers: they explain why skeletal muscle fiber-specific green autofluorescence can generate potential artifacts and show how to discriminate between autofluorescence and GFP signal. There is a (fake) green side and a dark side of GFP, i.e. the fact that its expression interferes with polyubiquitination. Those working on proteasome-mediated protein degradation should be very careful when ectopically expressing GFP, as shown by Baens et al.

To assess cell damage it is possible to exploit Evans Blue Dye, which is cell-impermeant unless the plasma membrane is damaged. A complete characterization of its use to label muscle fiber damage is described by Hamer et al. They tell you everything you wanted to know on EBD and you never dared to ask.

YACs, BACs, PACSs…are they Dr. Seuss’ creatures or carriers for successful generation of transgenic mice when transfer of large fragments of cloned genomic DNA is needed? Giraldo and Motoliu will tell you.

When we deal with myogenic cell cultures, we often obtain a mixed population of myotubes that have differentiated in the presence of a residual population of unfused myoblasts, i.e. syncitia vs single cells. The paper by Kitzmann et al. is not only a great JCB paper on cell cycle-dependent regulation of MyoD and Myf5 but also provides a trick to separate myotubes from myoblasts.

It makes no sense that we produce data if we do not know how to handle or to communicate them. I was struck by the news that about 50% of scientific articles contain errors of data analysis or reporting. C.H. Olsen reviews the use of statistics in articles published – yes, published – in Infection and Immunity and discusses the most common mistakes.

No comments:

Post a Comment