RESEARCH INTERESTS: Cellular and molecular mechanisms of striated muscle physiopathology

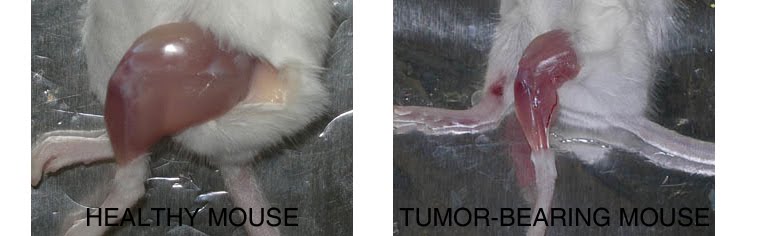

1. PHARMACOLOGICAL, PHYSICAL, AND NUTRITIONAL INTERVENTIONS AGANIST CANCER CACHEXIA: My laboratory is focused on different approaches to counteract cancer cachexia, including pharmacological (exercise mimetics), physiological (physical activity), and nutritional (supplements) interventions in humans and animal models.

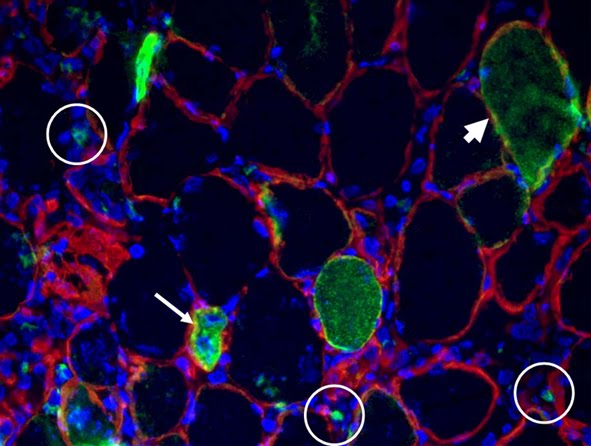

2. MYOFIBER MEMBRANE DAMAGE AND REPAIR: Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), is a lethal genetic, muscle-wasting disease, characterized by progressive muscle fragility and weakness. The muscle membrane repair mechanism (MRM) is an active resealing pathway involving vesicle-sarcolem fusion to “patch” the compromised plasma membrane and represents a possible target to counteract muscle wasting in DMD, in which the chronic cycle of muscle degeneration-regeneration plays a pivotal role in disease progression.

3. PATENTS AND TECHNOLOGY TRASNFER: I am co-inventor of a patented procedure to produce Hsp60-enriched exosomes with exercise-mimetic activity, a product that is, therefore, called Physiactisome. Patent: Physiactisome – «Procedure for the synthesis of HSP-containing exosomes and their use against muscle atrophy and cachexia» - patent n. 102018000009235 on 8/10/2018, deposited by Università di Palermo. Owners: Università di Palermo, Università di Roma La Sapienza, Nanovector Torino, Sorbonne Université. List of inventors: Valentina Di Felice, Rosario Barone, Antonella Marino Gammazza, Campanella Claudia, Cappello Francesco, Farina Felicia, Eleonora Trovato, Daniela D’Amico, Filippo Macaluso, Dario Coletti, Sergio Adamo, Gabriele Multhoff, Paolo Gasco. International publication number WO 2020/075004 A1. This product can be exploited against muscle atrophy, since it ameliorates muscle endurance and homeostasis. The presentation of the product and the corresponding Spinoff project (iBioTHEx) was awarded the third prize at the EIT JumpStarter Grand final, Riga, Latvia, 15-17/11/2019, Health category.

4. PHYSIOPATHOLOGY OF MUSCLE TISSUES: I contribute to discovering and explaining those mechanisms underlying pathologies of the striated and smooth muscle tissues; this activity is carried out at Sorbonne University by using genetic murine models.

RESEARCH INTERESTS: Tissue engineering of skeletal muscle

Background and rationale.

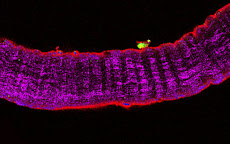

Tissue engineering lies at the interface of regenerative medicine and developmental biology, and represent an innovative and multidisciplinary approach to build organs and tissues (Ingber and Levin, Development 2007). The skeletal muscle is a contractile tissue characterized by highly oriented bundles of giant syncytial cells (myofibers) and by mechanical resistance. Contractile, tissue-engineered skeletal muscle would be of significant benefit to patients with muscle deficits secondary to congenital anomalies, trauma, or surgery. Obvious limitations to this approach are the complexity of the musculature, composed of multiple tissues intimately intermingled and functionally interconnected, and the big dimensions of the majority of the muscles, which imply the involvement of an enormous amount of cells and rises problems of cell growth and survival (nutrition and oxygen delivery etc.). Two major approaches are followed to address these issues. Self-assembled skeletal muscle constructs are produced in vitro by delaminating sheets of cocultured myoblasts and fibroblasts, which results in contractile cylindrical “myooids.” Matrix-based approaches include placing cells into compacted lattices, seeding cells onto degradable polyglycolic acid sponges, seeding cells onto acellularized whole muscles, seeding cells into hydrogels, and seeding nonbiodegradable fiber sheets. Recently, decellularized matrix from cadaveric organs has been proven to be a good scaffold for cell repopulation to generate functional hearts in mice (Ott et al. Nature Medicine 2008).

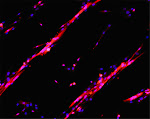

I have obtained cultures of skeletal muscle cells on conductive surfaces, which is required to develop electronic device–muscle junctions for tissue engineering and medical applications1. I aim to exploit this system for either recording or stimulation of muscle cell biological activities, by exploiting the field effect transistor and capacitor potential of the conductive substratum-cell interface. Also, we are able to create patterned dispositions of molecules and cells on gold, which is important to mimic the highly oriented pattern myofibers show in vivo.

I have found that Static magnetic fields enhance skeletal muscle differentiation in vitro by improving myoblast alignment2. Static magnetic field (SMF) interacts with mammal skeletal muscle; however, SMF effects on skeletal muscle cells are poorly investigated. 80 +/- mT SMF generated by a custom-made magnet promotes myogenic cell differentiation and hypertrophy in vitro. Finally, we have transplanted acellular scaffolds to study the in vivo response to this biomaterial3, which we want to exploit for tissue culture and regenerative medicine of skeletal muscle.

The specific aims of my current research are:

1) to increase and optimize the production and alignment of myogenic cells and myotubes in vitro;

2) to manipulate the niche of muscle stem cells aimed at ameliorating their regenerative capacity in vivo;

3) to develop muscle-electrical devices interactions. We plan to exploit the cell culture system on conductive substrates for either recording or stimulation of muscle cell biological activities, by exploiting the field effect transistor and capacitor potential of the conductive substratum-cell interface.

4) to better clarify the biological effects of Static Magnetic Fields. With the aim to characterize the molecular mechanism underlying the effects of SMF on cell differentiation and alignment we are exposing molecules and cells to SMF below 1T.

5) to produce pre-assembled, off-the-shelf skeletal muscle. We are seeding acellularized muscle scaffold with various cell types, with the goal to obtain functional muscle with vascular supply and nerves.

REFERENCES

1) Coletti D. et al., J Biomed Mat Res 2009; 91(2):370-377.

2) Coletti D. et al., Cytometry A. 2007;71(10):846-56.

3) Perniconi B. et al. Biomaterials, 2011 in press

Linked to the title there is a lesson for Master students (in English) on the mechanisms controlling skeletal muscle homeostasis.

OVERVIEW:

SKELETAL MUSCLE HOMEOSTASIS, HYPERTROPHY AND ATROPHY

The skeletal muscle tissue accounts for the majority of our body mass, nonetheless, the amount of skeletal muscle can vary significantly throughout life. There are specific mechanisms finely tuning the exact amount of muscle that we have at a given time.These are apparent in conditions far from homeostasis, i.e. when we have an excessive growth (hypertrophy) or reduction (atrophy) of muscle fibers. Throughout the presentation, I also try to state the case that not only muscle protein metabolism is important for controlling muscle homeostasis but also muscle stem cells support a "flow" of myogenic cells contributing to the maintenance of muscle fibers.

EXPERIMENTAL MODELS FOR STUDYING SKELETAL MUSCLE HOMEOSTASIS

Where I presents different approaches to study the regulation of muscle differentiation, growth and repair in vitro and in vivo.

MUSCLE ATROPHY, WASTING, CACHEXIA

Where I present different forms of muscle fiber atrophy and present in detail the features of the most severe form of muscle wasting, the syndrome of cachexia.

ENDURANCE EXERCISE & PROTEIN METABOLISM

Where I present some experimental data on exercise effects on muscle metabolism and homeostasis in physiological and pathological conditions.

MUSCLE REGENERATION IN PATHOLOGICAL CONDITIONS

Where I presents mechanisms whereby skeletal muscle regeneration is affected in cachexia, ultimately providing the molecular explanation for an important deficit in muscle regenerative capacity accounting for loss of muscle mass.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Glass D. 2003

Molecular mechanisms modulating muscle massMoseri V. 2010

Myogenin and calss II HDACs control neurogenic muscle atrophy by inducing E3 ubiquitin ligasesMusaro` A. 2004

Stem cell mediated muscle regeneration is enhanced by local isoform of Insulin-like Growth Factor 1Zhou X. 2010

Reversal of cancer cachexia and muscle wasting by ActRIIB antagonism leads to prolonged survival